Ellen is a visual artist and is currently studying sculpture under Robert Bodem. Among her exhibitions we mention: „Lux Æterna” (2022), „Metamorphosis” (2019) or „La fille d’Oscar” (2015).

1. Ellen, I would like to start off with some bio, seen through an artist’s eye: When did it all begin, what drew you to the visual arts and how do you see the entanglement between your life and your art?

It started about when I was 14, when I met a friend of my parents, who was a fashion designer. She’s a Belgian fashion designer called Kaat Tilley. Apart from making amazing clothes, she was also painting and drawing – she considered herself more of a painter than a fashion designer. When I saw her sketchbooks, something inside started to tingle really strongly. Wherever she went about, she spread beauty around her and that’s what I wanted to do as well. Then I started to draw on my own and at some point it got to painting; for some years I was just struggling by myself until I found that there was an academy in Barcelona that was teaching painting at an intensive level. And then I decided to go and study there.

[The entanglement between life and art] is quite direct, I can’t separate the two. The things that I see, the things that I feel directly influence what I make. I can’t lie about it. An example: when I’m painting or drawing the portrait of somebody, if I can’t have a connection or see the authentic beauty in that person I can’t paint them. I tried to draw a few people that have volunteered for me, but sometimes I noticed something dark about them and my portrait started resembling that; it’s not even in my control.

2. You have experience in drawing, painting and are now studying sculpture. What do you think each of these media has to offer, how are they different for artistic expression? Which one is closer to you?

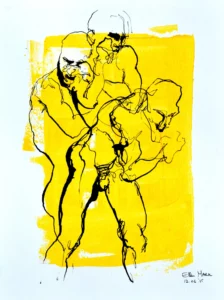

During the day, when I’m just living my life, certain images will just pop up in my head. It’s nice to be able to choose if this image would be best worked out in black and white, as a drawing, or in colour, as a painting, or now in 3D, as a shape. I’ve just started sculpture one month ago, so it’s a bit early to talk about this, but it’ll be really good to portray the dynamics between different people. There are a lot of sculptures of dancers and whatnot, but to me they are a bit lame. I think there are stronger things to be done there. What inspires me a lot about sculpture is multi-figure compositions. One of the first sculptures that I was drawn to was a sculpture by Guillaume Charlier in Tournai, Belgium. It was really well carried out, all these blind people being led by the little boy. All the faces and the hands and the feet, they were all really beautifully carried out, well proportioned, well related to each other.

3. You have a rather classical art training, which, to my mind, is necessary no matter what direction one chooses later on. Do you think this is the case or can you be a true artist without having solid knowledge of, say, anatomical drawing? Also, what do you think the golden ratio is between technique and spirit in a piece of art?

I think each person has to decide for themselves whether they need it or not. There are a lot of great artists that have not had any training, like Séraphine de Senlis or Van Gogh. There’s no standard answer. [Learning technical aspects] is definitely helpful; you can learn it on your own, but it’s going to take a long time. I was so happy to be in Barcelona and learn so much in two years and a half. I was constantly energy-deprived, but what I did there in two years and a half would have taken me twenty years. There I was, taken by the hand by people who had gone through this all. They couldn’t prevent me from falling into pits but they were able to warn me about them. After that, the visions that you want to make are going to come out more easily, because you wouldn’t be struggling so much with the material part of it.

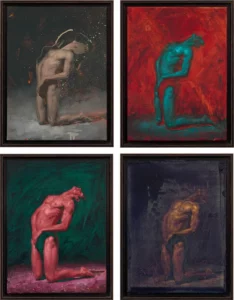

4. Many of your paintings and drawings have a full and grounded sensuality, in the most literal sense: you depict faces and bodies realistically, contorted in a state of pleasurable or painful tension, as if to photographically capture the particular and unseen intensities of the human spirit through its body. You were also telling me at some point that you are fascinated by facial expressions and that no face is uninteresting to you. Would you care to elaborate on that?

No, I think you’ve put it pretty well! [we both laugh] I don’t really know why it’s so enjoyable, but I love watching people’s faces and trying to recreate them. It brings me so much joy! It might be a secret mission of mine. [Ellen’s usually broad smile broadens even more] I think everybody is born with an objective and talents, and an aim to put those talents to use for a greater good. For me, it feels like I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing. That very thing brought me to tears when I arrived in Barcelona. I didn’t realize it at the moment, but the reason it brought me so much emotion was that I was in the right place at the right time, learning exactly what I needed to learn in order to carry out my mission. It’s good to feel that you’re doing what you are here to do.

5. Judging by your approach, you are quite the rare bird in today’s art scene, which is much more preoccupied with figurative and abstract art. Why does someone today go back to styles, techniques and subjects oftentimes regarded as outdated or ‘too traditional’?

I think the art world is still stuck a little bit – they move slowly. They may still be very big on conceptual art, but they are catching up [to the return of artists to realism]. There are always movements: the Impressionists also didn’t make their movement established from one day to another. But there are increasingly more schools teaching classical realism, which means that more and more artists feel that they need to have a technical basis to start from. With more artists doing that, the galleries will eventually follow suit. When I talk to older artists, they say that if they had been doing the kind of things I’m doing now 20 or 30 years ago, they would’ve just been spat out by the system. I do feel that people have had to chew on empty nonsense for a while – and some of it makes me pretty angry. What is this nonsense? Who would buy such things? When we’ve had that banana with the duct tape, I thought: “Ok, we’ve hit the low point now, can we start making sense of this things again?”

6. Since we’re talking tradition, I’d like to hear more about the influences that guided your journey – both from the past and the present.

But there are so many! I mean, recently you witnessed the Vincent van Gogh craze. Suddenly, I understood. I thought: have I been blind all this time? But before, I didn’t care. In a museum, I would just walk past his work. So it’s all about like resonance, I think. At some point you just resonate with a certain artist and his work. And then time passes by, you change and it doesn’t resonate anymore. I used to love Klimt. And there’s still a princess part of me that enjoys his works, but it’s not the same as it used to be.

Kaat Tilley – because of her I started drawing and painting. And somehow I can’t forget about that. The first love you can’t forget.

7. The other day were we chatting about the art world today and how it is very difficult to permeate it if you’re not willing to sacrifice at least part of your vision – what I mean by ‘permeate’ here is have exhibitions, become known, sell. You have already gone through a couple of exhibitions, sold multiple pieces and even published two albums (one of which is sold off on your website!). It seems like you’ve managed to preserve your vision. Could you tell us more about how this came to be?

I don’t know! I kept making things that I wanted to make and they found a place outside of the gallery circuit. I’ve mostly exhibited in places like cultural centers; my last exhibition was in a law firm building, a beautiful Art Nouveau building that used to be part of a museum in Belgium. This firm kept doing exhibitions biannually, so the exhibition lasted six months. I don’t plan these things, but I have trust: I had actually begun making the series well before they approached me. I was making it and I thought: “Well, it’s going to end up somewhere, we’ll see”. And it basically sold out, 60 or more paintings, although the art wasn’t that easy [to have in one’s house].

8. Among the things that we talked about, there was the subject of artistic taste. You mentioned then that only quite recently did you develop a liking for Van Gogh and that you have an adversity for Bacon or anything too gory. How do you think artistic taste develops and what is the balance between training your eye, so to speak, and a natural taste for something?

It’s hard to answer that question because I don’t know what it’s like not to be interested in art. Well, I think it’s mostly about what matters to you. If something doesn’t matter to you, then you’re not going to have attention for it. But it can also happen that in your life you meet somebody or something happens to you and then maybe a radical eye-opening ensues. And it’s also about nature versus nurture. For example, when I first arrived at the school, my main teacher was very surprised that I’d never heard of Sargent. He thought he’s the greatest painter ever. And so when I looked him up, it was like nice brushwork. But to me, the essence, it seemed like very empty images. And I think that’s a very personal thing, whether you favor narrative or whether you favor aesthetics. But we need everything. We need both. But for me, the sweet spot is when both of them hit it at the same time.

9. Does the function of art have anything to do with beauty or harmony (or the opposite, of which – in a gross approximation – Bacon could be considered an exponent)?

Well, I think art can have many functions, depending on the maker. Some artists are meant to provoke and break boundaries. Other artists or other paintings or works are more meant to draw attention to, for example, harmony and beauty, or carry out that feeling. I think maybe more importantly than what is actually portrayed is the energy that emanates from a work. For me, I think my mission is more to draw attention to certain things that have positive vibrations, like beauty and harmony. I’m not such a provoker, but I can see the need of that in society, but it’s not my task. I’ll leave that to others. I want to get really close to people somehow. I want them to feel like they can recognize a part of themselves in my work.

It’s that feeling [of community and communion] that also helps me. I’m just being used really. I’m not really doing it. It’s all sort of happening through me, but I think it’s that very feeling of connection that is making me do all of those things. I make an observation in the model, but then, when I’m placing it, it’s like I almost get out of my body. I’m just working from my feeling. Nor do I look at it. I don’t focus on the work, but I focus on the feeling. So I’m looking at my work in a blurry way, from the inside.

10. You have very kindly shared with us some of your delightful artwork. Could you tell us more about your albums, exhibitions and what is next?

I’m at a point right now where I’m gathering new material and inspiration and ideas for upcoming shows or series – I tend to always work in series that tell a story. A story starts to grow like a plant: at some point you notice something that you’ve never noticed, a love for something that before you didn’t feel. I’m sure I’m going to keep doing exhibitions, because it’s my way of telling stories. So as soon as the new story becomes clear, then I’ll start working. When I finished this last series in December, I felt I had ended a cycle and I had no idea what was coming after that. I’ve painted enough solitary people. I think it’s time for some group dynamics. [Not knowing what is going to happen next] requires you to have patience. You can just be open to it, but you can’t force it to come. You need to give it time and space to develop and unravel itself.

11. Finally, any words of wisdom for young aspiring artists?

People keep telling me that at some point I’m going to have to go with the galleries, and I’m going to have no choice. It’s probably going to sound lamer than I intended to, but your feeling is your best compass as to where you need to go. There’s no standard way of doing things; if you follow your gut feeling of how things would work out best for you without forcing things, then somehow life is going to find a way. In our society, everybody’s forcing their way through life. I think there’s a better way that’s more in harmony with your strengths and capabilities and your talents, which then will find the right time to come to fruition. So give more trust to life, to make things emerge.

You can learn more about Ellen and her work here.

Image: Ellen at work

What a beautiful story! I met Ellen twice and saw her work. A beautiful person and amazing tableaux she makes. I am speechless.